Introduction

Ancient Greece, a land rich in culture and tradition, birthed some of the most enduring myths known to humanity. At the heart of this myth-making process were the storytellers—bards, poets, and orators—who played a pivotal role in shaping the narratives that defined not only the ancient Greek worldview but also their values, beliefs, and identity. Through their tales of gods, heroes, and fantastical creatures, these storytellers crafted the very fabric of Greek society and left a legacy that continues to resonate today.

The Historical Context of Storytelling

Before delving into the nuances of storytelling in Ancient Greece, it is important to understand the historical and cultural context in which these narratives flourished. Approximately from the 8th century BCE, storytelling in Greece transitioned from oral traditions to written forms, especially with the advent of the alphabet. This period saw the rise of two monumental figures in literature: Homer and Hesiod.

Homer, traditionally considered to be the author of the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey,” composed epic poems that encapsulated the values of heroism, honor, and the human experience. Hesiod, on the other hand, focused on the origins of the gods and the moral lessons to be learned from them in his works such as “Theogony” and “Works and Days.” These early storytellers not only entertained but served as cultural historians, preserving the beliefs and practices of their time.

The Function of Myths in Society

Myths served several essential functions in ancient Greek society. Firstly, they offered explanations for natural phenomena. The Greeks personified elements of nature as gods and goddesses—Zeus for the sky, Poseidon for the seas, and Demeter for the harvest. Through stories of divine actions and interactions, the unpredictable forces of nature were made more understandable.

Additionally, myths acted as vessels for moral and ethical lessons. The characters in these stories often faced moral dilemmas, showcasing virtues such as bravery, wisdom, and justice, or conversely, flaws like hubris and deceit. Through the trials of characters like Odysseus or the tragic figures of Sophocles, audiences were able to reflect on their own lives and the moral choices they faced.

Lastly, myths played a crucial role in establishing social norms and identity. Stories surrounding the heroes of the Trojan War, for instance, encouraged unity and valor among the Greek city-states. They celebrated shared ancestry and cultural heritage, fostering a sense of belonging that was crucial in a time when city-states often vied for power.

The Storyteller as an Artist

The role of the storyteller went beyond mere narration; they were artists who crafted intricate tapestries of language and imagery. Poets like Homer utilized meter and rhythm to make their tales memorable. The oral tradition allowed for improvisation and adaptation, varying from one performance to another. This adaptability made each rendition unique, while the core themes remained intact.

Moreover, these storytellers often drew upon collective memory to weave their narratives. They relied on a rich tradition of oral history passed down through generations, infusing contemporary issues and sentiments into ancient tales. Thus, the act of storytelling became not just an art form but a medium for continuous dialogue between the past and present.

The Role of Festivals and Cult Rituals

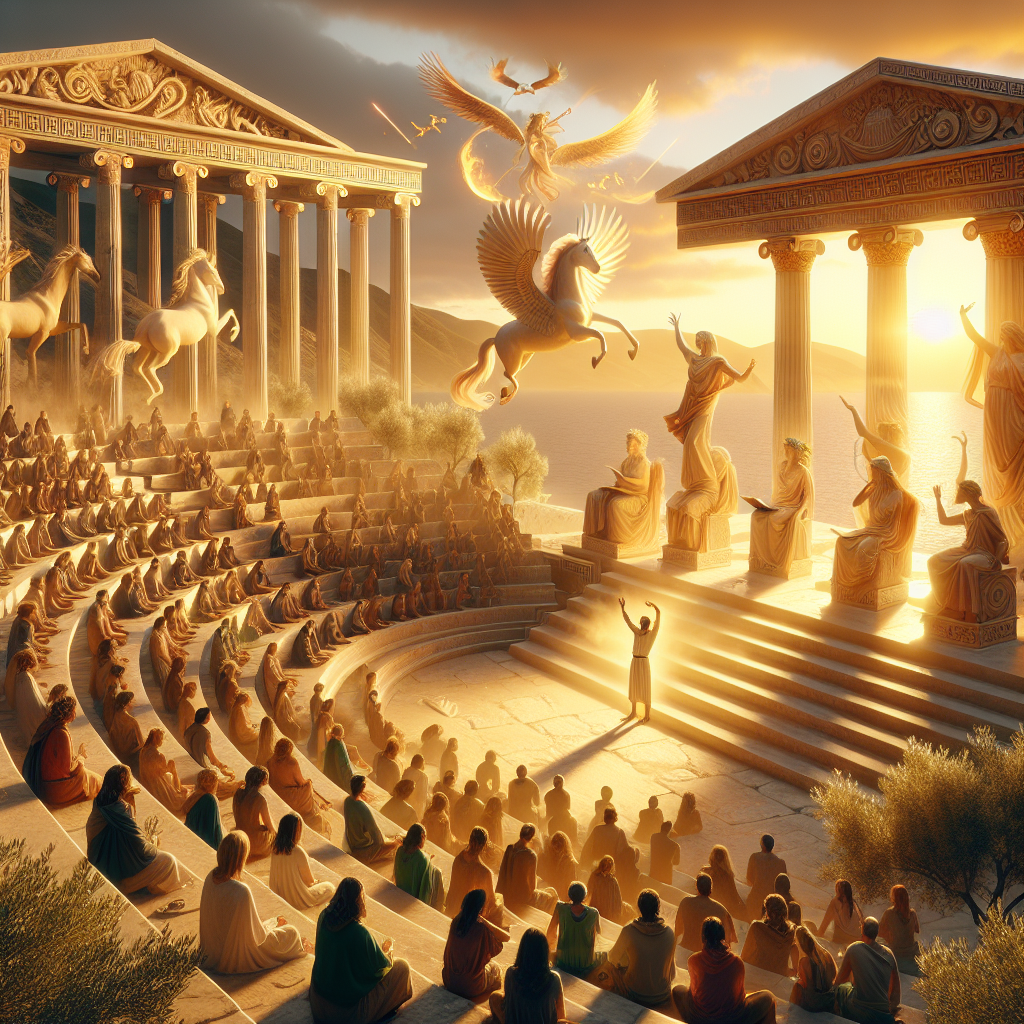

Storytelling in ancient Greece was not confined to solitary performances but was often embedded in communal activities and religious festivals. The Panhellenic festivals, such as the Olympic Games and the City Dionysia, included competitions in poetry and drama as integral components. Through these gatherings, myths were not only recited but enacted, bringing the stories to life in a shared communal experience.

During the City Dionysia in Athens, tragic plays and comedies often depicted mythological themes. Playwrights like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides utilized myth to explore complex human emotions and societal issues, pushing the boundaries of traditional narratives. The audience, comprising citizens from various city-states, participated in a collective experience that reinforced their cultural identity.

These communal experiences also served a more practical function; they facilitated social cohesion and provided a platform for discussion about moral values, governance, and personal conduct. In this way, storytelling became a collective enterprise, deeply interwoven with the fabric of community life.

The Evolution of Myth in Written Literature

With the advent of written literature, the role of the storyteller evolved. While early myths were fluid and easily changed through oral recitation, written texts helped solidify certain versions of myths. This shift led to the establishment of canonical texts. However, it also opened the door for reinterpretation and analysis.

Hesiod’s “Theogony,” for instance, established a genealogical framework for the Greek pantheon, allowing later philosophers and writers to build upon or challenge these narratives. The flexibility of myth in both oral and written forms permitted continual engagement with cultural narratives, creating a dynamic dialogue that reflected changes in society, philosophy, and politics.

Conclusion

The storytellers of ancient Greece were more than mere entertainers; they were vital architects of cultural identity, historians, and ethical guides. Through their art, they created myths that explained the world, defined moral frameworks, and fostered community ties. Even as storytelling evolved from oral traditions to written narratives, its central role in shaping Greek society remained steadfast.

Today, the myths of ancient Greece continue to captivate audiences around the globe, reminding us of the enduring power of storytelling. The legacies of Homer, Hesiod, and the countless unnamed bards resonate not just in literature but in everyday life, as we continue to search for meaning in our own stories. Each generation, like those before, adds depth to this magical tapestry of myths, ensuring that the art of storytelling remains an essential human endeavor.